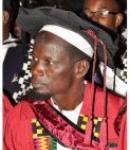

Issaka Ahmadou was born to farmers in a small village called Faram on the southern lip of Niger some 800 kilometers east of the capital Niamey. His mother gave birth to 11 children. Ahmadou was her sixth. Five died four in childbirth.

His father whose name was Issaka refused to send his children to school. Like many in the area he said the primary school was a "white man's school" that should be avoided; no whites were physically present at the school but everyone called it the school of the whites because the French during the colonial period built it. But when Ahmadou was seven years old the school teachers told the village chief that all seven-year-olds must attend class that year. The teachers were powerful and the obedient chief carried their message from home to home. Ahmadou's parents sent him and him alone to school the next day. When Ahmadou returned from the first day of classes his entire family came out to greet him. "All my sisters were crying because they put me in school " he remembers now 34 years later. "I said 'Why are you crying?' They said 'You are going to school now.' I was just a boy so I didn't understand anything. I told them I just was going to school to play." He finished primary school then secondary school and then earned his bachelor's and master's degrees at universities. Now the only child of Issaka from Faram who went to school is one of eight AGRA-sponsored researchers beginning doctorate studies at the University of Ghana Legon. Ahmadou sometimes wonders about his fortune and the ill fortune of his brothers and sisters. But he doesn't think twice about the nature of his work and why he decided to study crop sciences. As a researcher for the National Institute of Agronomic Research (INRAN) in Kollo south of Niamey he has been working on breeding new varieties of millet for the last four or five years. Millet is a staple food in Niger but the yield is very low - about 400 to 500 kilograms per hectare. Ahmadou who is married with three children and a fourth on the way now hopes to breed a more productive millet seed. If he succeeds he knows it will help most of his country - farmers comprise 80% of Niger's workforce - and it will help his family too. His family grows millet sorghum and beans. "I've always loved agriculture. I have worked in the fields as a boy with just my arms nothing else with no modern instruments. It is very hard work. Most people still work this way. I hope to help them and give them something to take to the fields."